Key words :

future energies,

peak oil

,cantarell

,carbon dioxide injection

,enhanced oil recovery

,eor

,kern river oil field

,nitrogen injection

,oman

,steamflooding

Will Enhanced Oil Recovery Be An Oil Supply Savior?

24 Mar, 2010 07:01 pm

Oil supply optimists often say that the application of enhanced oil recovery techniques to existing and future wells will vastly expand oil reserves and oil production. The trouble is these techniques aren't new, and they are already being widely applied. That means current oil reserves and production already reflect any effect they have had.

To read ExxonMobil Corporation's website one might get the impression that the world's largest oil and gas company has begun only recently to employ enhanced oil recovery (EOR) techniques. If that were true, this industry bellwether might have been able to say that these techniques will have a substantial effect on the future flow of oil. After all, the claim for EOR is that it could potentially double the amount of oil we can get out of the Earth--from the current one-third to two-thirds or so of the original oil in place. The implication is that not only will future wells yield more of their oil than previous ones, but that far more oil can now be harvested from existing wells.

To read ExxonMobil Corporation's website one might get the impression that the world's largest oil and gas company has begun only recently to employ enhanced oil recovery (EOR) techniques. If that were true, this industry bellwether might have been able to say that these techniques will have a substantial effect on the future flow of oil. After all, the claim for EOR is that it could potentially double the amount of oil we can get out of the Earth--from the current one-third to two-thirds or so of the original oil in place. The implication is that not only will future wells yield more of their oil than previous ones, but that far more oil can now be harvested from existing wells.The big problem with this thesis is that EOR is already being widely applied--so much so that the Oil & Gas Journal will sell you its most recent worldwide survey of EOR projects for only $330. You can get the full historical database all the way back to 1986 for a mere $1,100. (Hint: Both contain more than a few entries.)

The three main types of EOR are gas injection, steam (both cyclic stimulation and flooding), and chemical injection, and they've been around for a long time. The poster child for EOR among the oil optimists is the Kern River Oil Field near Bakersfield, California. Kern was discovered in 1899. As production waned, steamflooding was introduced in 1964. In 1961 production was about 19,000 barrels per day. By 1966 it had risen to 53,000 barrels per day. Production reached its peak at 141,000 barrels per day in 1985. Production continues today at around 80,000 barrels per day.

The Kern River steamflood has proven how well EOR can work in some situations. But as any reader will deduce, the results are already reflected in current production and reserve estimates. Steamflooding has been in use for a very long time.

Natural gas injection is also an old technique used to maintain reservoir pressures. It has been used continuously, for example, at Alaska's Prudhoe Bay Oil Field which began shipping oil in 1977.

Nitrogen injection is newer, but has been used, for example, since 2000 on the huge Cantarell Field in the Mexican portion of the Gulf of Mexico. Results were excellent at first. But the subsequent crash of production at Cantarell has called into question whether this form of EOR merely hastened production without increasing ultimate recovery.

The same issue has been raised by another technique called maximum recovery contact wells, which is often grouped with EOR. The technique worked superlatively for a while in Oman's largest oil field only to lead to a precipitous crash in production later.

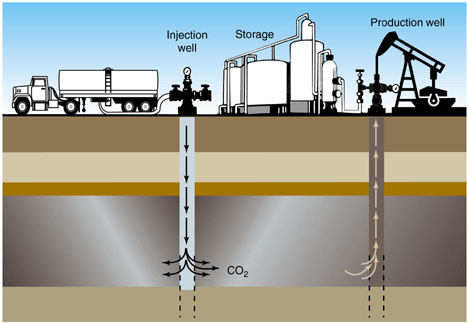

Carbon dioxide injection has also been used successfully, but supplies are expensive if they are not near the field. The newest of the major EOR techniques involves inoculating reservoirs with microbes that will make the oil flow more freely. It looks promising.

Oil company sources tell me that indeed these techniques are used wherever practical. Limitations include high capital and operating costs. For example, Cantarell's nitrogen injection system cost $6 billion to build. Other limits may result from the existing infrastructure. For instance, will that infrastructure be able to handle additional production? And, if not, what would it cost to upgrade it?

High costs almost always mean high energy inputs. Even if the capital and expertise is available, it may cost more energy to implement an EOR program than will be gained from the extra oil. Inevitably, the energy return on investment for oil obtained using EOR will be lower, often far lower, than oil obtained using standard methods.

Oil supply optimists often talk about doubling average recovery from oil wells. But B. J. Doyle, vice president of operations for a small Houston-based oil and natural gas exploration company, cautions against such talk. Every reservoir is unique. This means that 1) many reservoirs will simply not benefit from EOR and 2) the increase in recovery when EOR is applied can vary widely.

In addition, Doyle says, there are fields where the techniques won't be applied until small operators take over. After large oil companies get the majority of oil out of a field, they often find it's not worth their while to continue pumping. Frequently, they sell their interests to smaller operators who have the willingness and patience to squeeze out the final barrels using a variety of techniques, some of which wouldn't necessarily qualify as EOR.

In places such as the United States and Canada this happens as a matter of course. That's why these countries have so many operating wells, many of which pump fewer than 10 barrels a day. But this pattern of exploitation in mature oil fields is only happening in these countries because they allow private ownership of oil rights. In places such as Nigeria, Iran and Saudi Arabia, private companies cannot simply purchase or lease mineral rights from the owner because the owner is the government. In Iran and Saudi Arabia, the government has total control over the oil industry. There is no entrepreneurial class of small operators able to take over largely exhausted fields and revive them. That means that in many of the most oil-rich places in the world, EOR on the scale practiced in the United States and Canada will probably never become a reality.

Energy writer Chris Nelder gives us perspective on what we can expect from EOR. He writes that history shows us that EOR "does not affect the date of the peak, nor the peak rate of production. It typically just extends the 'tail' on the back end of the curve and increases the ultimately recoverable total."

Even with all these caveats, I think we can concede that EOR will add to proven oil reserves in the future and likely cushion the decline in oil production after world output peaks. But given the historical record of EOR, it is unlikely these techniques will prove to be the savior of oil production rates that the oil supply optimists would have us believe.

-

12/12/12

Peak Oil is Nonsense Because Theres Enough Gas to Last 250 Years.

-

05/09/12

Threat of Population Surge to "10 Billion" Espoused in London Theatre.

-

05/09/12

Current Commentary: Energy from Nuclear Fusion Realities, Prospects and Fantasies?

-

04/05/12

The Oil Industry's Deceitful Promise of American Energy Independence

-

14/02/12

Shaky Foundations for Offshore Wind Farms

Read more

Read more

* The high capital costs for EOR would be problematic, were it not for the existance of a futures market. When oil prices are high, EOR operators are able to insure a payback for their venture by shorting the long term price of oil. If oil stays high, they recover their money selling expensive oil. If it crashes, they recover their money through contracts. Either way, their funding is assured, so long as the well produces.

* The EROI of EOR projects is not the critical factor you think it is, as the "input energy" is not necessarily oil. Currently, natural gas is priced at 1/4 the energy equivalent of oil.

* Much of the EOR bottleneck has been the availability of CO2. There is an overabundance of man made CO2 in the form of coal and natural gas. This CO2 is more expensive to tap than naturally occurring CO2 wells, but when oil moves over $80 a barrel it becomes profitable to do so.

* Your assumption that the Saudis won't employ EOR techniques seems highly speculative. In fact, the Saudi wells are extremely close to natural gas supplies. They have so far proven to be very sophisticated in developing their oil resources, and it would be a surprising indeed for them to leave money in the ground.

That said, your ultimate conclusion is probably accurate. EOR requires high oil prices, and thus EOR is unlikely to create a glut of inexpensive oil. Rather, it will act as a ceiling on oil prices, insuring that production stays at a high plateau for many years.

1) PJC assumes that well operators will find the perfect hedging tool in the futures markets. This is problematic for several reasons. First, it is difficult to predict exactly what kind of recovery an operator will obtain until he or she actually applies EOR techniques. Thus, the operator may hedge too much or too little oil, and both situations have their perils. Second, the contracts available tend to reflect light oil prices which do not always move in lockstep with heavy oil, which is typically what the EOR operator is attempting to hedge. Third, prices in future markets may move rapidly before the operator is ready to deliver oil to the market, that is, while he or she is building the EOR infrastructure. This means a market moving against an operator may result in substantial margin calls which could deplete very rapidly the operator's cash position and force him or her to close out positions prematurely at a substantial loss. Fourth, hedgers typically close out short positions without making delivery and instead sell into the physical market. It is not always easy to coordinate these two events in volatile markets so that the effect of the hedges works the way the operator wants them to. Finally, costs for EOR operators are not constant. They can certainly attempt to fix the price of their oil deliveries using the futures market, but they will have a much harder time hedging the costs of their inputs.

I'm not saying that the futures markets aren't useful. But I think PJC portrays them as far less risky for hedgers than they are.

2) PJC is conflating price and EROI. Let me address both since they are separate issues. PJC again assumes that input prices will remain low over time. Given the volatile history of one of the major inputs for EOR, natural gas, I think this is a perilous assumption. Input prices, however, tell us little about EROI. The embodied energy in inputs changes only very slowly over time and price spikes or crashes due to changes in demand do not reflect changes in EROI.

3) In general I agree with PJC about carbon dioxide injection.

4) PJC claims that I wrote that the Saudis won't employ EOR techniques. This is I acutally wrote: "That means that in many of the most oil-rich places in the world, EOR on the scale practiced in the United States and Canada will probably never become a reality." Entrepreneurs with innovative ideas and the chance to obtain large rewards for their efforts are the backbone of extensive EOR in the United States. Naturally, state-owned companies can and do engage in EOR. But I do not think they will ever achieve the kind of thorough application we see in the United States where small fields and low-volume wells attract niche operators because of the incentives available to them and result in innovative approaches and exceptional efforts. I just don't see this happening within the bureaucracy-laden national oil companies of the world on as broad a scale as in the United States for the reasons I stated above.

However, EOR (and GTL) critics seem to imagine a world in which hedging doesn't exist, and in which processes that are capital intensive and/or rely on multiple feedstocks are never undertaken because of fear of future market fluctuations. This is silly. When spot prices are overwhelmingly in your favor, you engage in long term contracts to minimize future risk, and use these contracts to your benefit when raising capital. Of course the risk is never fully 0%, but it's incorrect to imagine a world in which long term capital planning has no method of coping with price variability.

Re: EROI - this ratio is interesting, but at some point it's meaningless. Wind power has an incredibly low EROI if you consider how little of the available wind energy is turned into electricity. Similarly, hydro power captures only a small fraction of the potential energy lost when water moves downhill. The issue is not just EROI, but EROI relative to the cost of the input energy. When natural gas is cheap (as it is now) then it is profitable to engage in projects that have an EROI of less than 1 (i.e. a net loss in energy) so long as the input energy is gas and the output oil. It is the opportunity for profit that determines which projects are undertaken, not the EROI.

PJC is correct that projects in the energy industry are undertaken when they are deemed profitable, regardless of the EROI. I have never said anything to the contrary. Corn ethanol is a prime example of a process that produces no net energy and yet is profitable because of very large government subsidies. I agree that EOR projects will move ahead under the right conditions and concluded as much at the end of my piece. Wherever operators believe they can make a profit, even under risky and difficult conditions, they will proceed to build and manage EOR projects.

PJC still doesn't seem to understand EROI. This ratio does NOT measure the amount of the available energy in wind or falling water passing by wind generators or dams and divide it into the actual power produced. EROI measures the energy inputs from society in the form of the embodied energy in materials (i.e. the energy needed to mine, refine, manufacture, transport those materials); the energy needed to put them in place as in the construction of a dam or the construction of footings for and erection of a wind tower; and the energy used to service these structures. It then divides this total into the lifetime energy output of such structures. By this measure hydroelectric dams have fairly high EROI of around 11. And, wind generator studies show an EROI of around 20. Of course, for individual dams and wind turbines this ratio varies widely. But the EROI for wind is comparable to that of conventional light oil and thus very competitive in today's energy environment.

"Oil supply optimists often say that the application of enhanced oil recovery techniques to existing and future wells will vastly expand oil reserves and oil production."

Of cause, future wells will vastly expand oil reserves if industry uses breakthrough exploration technology http://binaryseismoem.weebly.com

With new exploration technology (patented invention US 7,330,790)?we could make up to three times more oil and gas discoveries than when using conventional technology. And the fact that new technology won't need more investments is also very important. It can significantly mitigate?world energy problems.

The technology is designed and successfully tested in the Barents and the Black Seas as well as in the Gulf of Mexico

We have injected all sorts of caustic chemicals, detergents and toxic cocktails into the ground with the goal of making heavy thick oil flow better through a formation -- and now the public is blaming these toxic EOR and fracking cocktails for contaminating their water.

That is why I am happy to inform everyone that a new, non-toxic chemical injectant called EncapSol can cost-effectively break the molecular bonds that bind oil to sand, clay rock and water molecules -- cleanly releasing this oil and encapsolating it for easy-flow to an exit well.

See it work in these videos at :

www.encapsol.com/media

It can work in liquid form with water flooding or in gasous form for EOR injection.

What is truly intriguing is that the Encapsolated oil solution is heavier than water and heavier than oil -- so it can sink (and contact, release and collect oil as it falls through a formation ) or be moved laterally through a formation from a high pressure injection zone to a lower pressure exit well.

You bring up the Encapsol plus oil mixture to the surface and use the EncapSol oil separation machine to remove the oil for sale and recycle the EncapSol solvent for reuse downhole, saving money on chemicals which is a huge cost obstacle suffered by most other tertiary EOR methods.

I believe EncapSol can change the EOR business by significantly increasing downhole oil recovery rates and enable America to re-open all of its old and abandoned oil fields that still have millions and billions of stranded oil left for EncapSol to recover.

People often confuse the energy in the oil with the energy used to extract the oil. I.e. they say "if you are burning 1 joule of process energy to extract 0.8 joules of oil, the EOR operation makes no sense". Not so, the process energy could be cheaply and easily obtained, from natural gas, or in the future, from solar or nuclear.

One role of EOR is transform energy from a form of relative abundance (coal, natural gas, solar) to one of scarcity (oil). The net production of energy is not actual required.

Thus, if the supply of natural gas expands, then lower EROI EOR operations can become profitable. The price in natural gas is dropping, in part because the marginal cost of extraction is dropping unconventional gas.

PJC is correct that we may at some point in the future decide that it is worthwhile to extract oil that gives us no net energy because we can turn it conveniently into a liquid fuel suitable for the current infrastructure. In that case, oil would not be an energy source, but an energy carrier. But, I'm not sure that we would continue to do this for long since we already know how to turn natural gas and coal into liquid fuels directly. Why use the energy in these fuels to extract yet another unrefined product with very low EROI, when we can go directly to liquid fuels from these two sources? Of course, we would have to change the infrastructure to accommodate either natural gas compressed vehicles or build plants that can give us liquid fuels from natural gas or coal suitable for the current infrastructure. This is no small task. But if natural gas or coal are as abundant as PJC believes--not something I necessary buy--then it would be worthwhile to make the transition.

I guess the area in which we differ is in whether EOR will slow the decline in oil production, or prevent a long term decline from occuring. If the oil production begins to decline consistently, the price will likley shoot up to exorbitant levels (+$200 or higher). This seems unlikley, given that such a wide variety of supplier seems to have marginal costs of extraction at $80 or below.

So the most likely outcome seems that oil production will meet global demand for $80-$100 oil for many years to come, which would result in a production plateau.

This is all assuming Iraq fails to come on line. If Iraq starts delivering, and fails to heed OPEC production quotas, then we are looking at a return to the 80s, with oil in the $20s and small US domestic players going bankrupt.

I can tell you that there are special tax breaks for EOR in the U. S. tax code. How they relate to the depletion allowance I'm not sure.